Angular is often used for the frontend of large, mission-critical solutions. In this environment in particular, it is particularly important to ensure that the architecture is easy to maintain. However, it is also important to avoid over-engineering. Current features such as standalone components or standalone APIs help.

In this two-part series of articles, I show how you can reconcile both requirements. The first part highlights the implementation of your strategic design. The specified architecture is enforced with the open-source Sheriff project.

The examples used here work with a traditional Angular CLI-Project but also with Nx. In the latter case, we recommend starting with an Nx Standalone-Application to keep the architecture lightweight and folder-based.

The Guiding Theory: Strategic Design from DDD

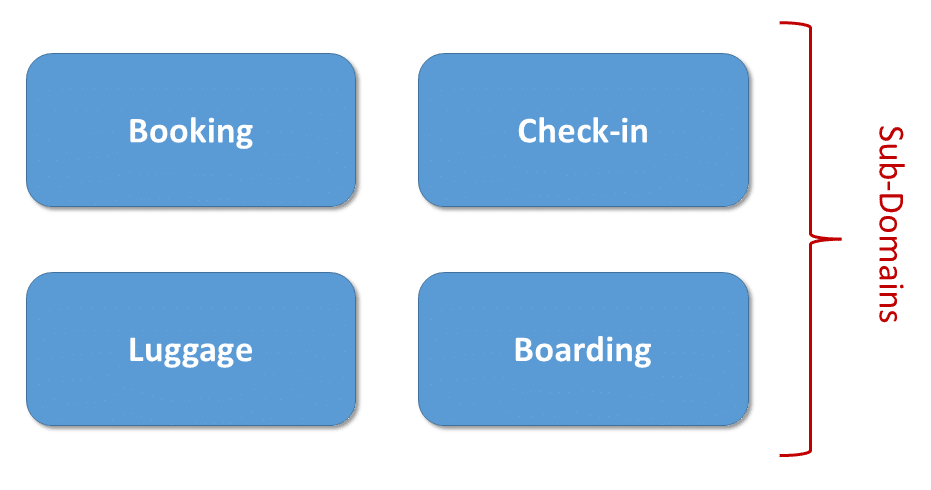

Strategic Design, one of the two original disciplines of Domain-driven Design (DDD), has proven itself as the guiding theory for structuring modern frontends. The main point here is to break down a software system into various sub-domains. For example, in an airline, you might find the following sub-domains:

Identifying individual domains requires a look at the business processes to be supported. The interaction between developers and architects on the one hand and domain experts on the other is essential. Workshop formats such as event storming Event Storming, which combine DDD with ideas from agile software development, are ideal for this.

he discovered sub-domains are translated to so called bounded contexts. While the sub-domain represents the a part of the real world ("problem space"), the bounded contexts are the counterpart in the software system ("solution space"). Each bounded context has a model of it's own representing a very specific part of the sub-domain within the software system. That means a flight in the boarding context is not necessarily the same as a flight in the booking context. This prevents an overly complex on-size-fits-all model and makes sure that each context decribes the respective view to the real world in an accurate way.

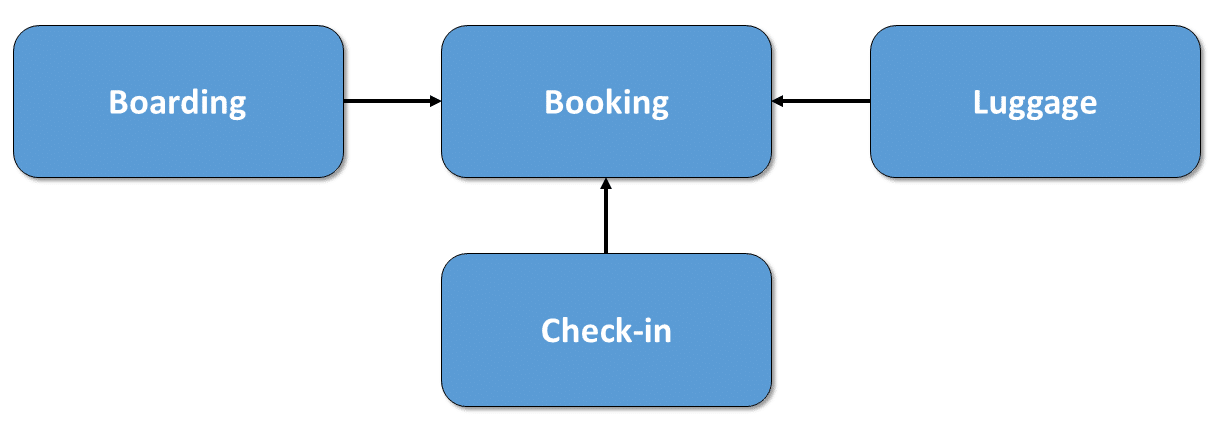

A consequence of decomposing a system into bounded contexts is also low coupling and thus an improved maintainability: For instance, Booking could only publish a few selected services in the example shown. Alternatively, information about booked flights could be distributed via messaging in the backend. In larger projects, it is common to assign one (or more contexts) to a separate sub-team in order to follow Conway's Law.

Ideally, there is one bounded context per sub domain, but -- for technical or organisational reasons -- you can also decide to break down a sub-domain into several ones. A context map represents the relationships and dependencies between individual contexts:

Strategic Design provides several Context Mapping Patterns for designing the relationships between bounded contexts. For instance, a bounded context could export selected aspects via a service. Also, a bounded context could protect itself from changes in another one by shielding it via an anti corruption layer that translates between the different models.

Transition to Source Code: The Architecture Matrix

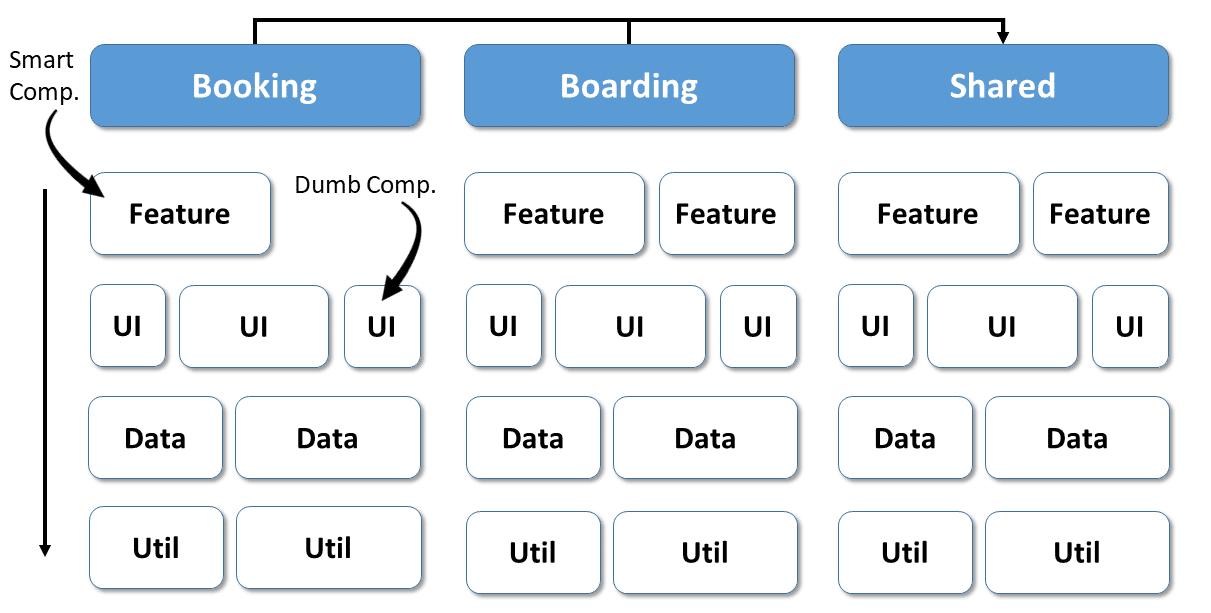

For mapping in the source code, it makes sense to further subdivide the individual contexts into different modules:

A categorization of these modules increases clarity. Nrwl suggests the following categories (originally for libraries), among others, which have proven helpful in our daily work:

A categorization of these modules increases clarity. Nrwl suggests the following categories (originally for libraries), among others, which have proven helpful in our daily work:

- feature: A feature module implements a use case (or a technical feature) with so-called smart components. Due to their focus on a feature, such components are not very reusable. Smart Components communicate with the backend. Typically, in Angular, this communication occurs through a store or services.

- ui: UI modules contain so-called dumb or presentational components. These are reusable components that support the implementation of individual features but do not know them directly. The implementation of a design system consists of such components. However, UI modules can also contain general technical components that are used across all use cases. An example of this would be a ticket component, which ensures that tickets are presented in the same way in different features. Such components usually only communicate with their environment via properties and events. They do not get access to the backend or a store.

- data: Data modules contain the respective domain model (actually the client-side view of it) and services that operate on it. Such services validate e.g. Entities and communicating with the backend. State management, including the provision of view models, can also be accommodated in data modules. This is particularly useful when multiple features in the same context are based on the same data.

- util: General helper functions etc. can be found in utility modules. Examples of this are logging, authentication or working with date values.

Another special aspect of the implementation in the code is the shared area, which offers code for all contexts. This should primarily have technical code – use case-specific code is usually located in the individual contexts.

The structure shown here brings order to the system: There is less discussion about where to find or place certain sections of code. In addition, two simple but effective rules can be introduced on the basis of this matrix:

- To enforce low coupling, each context may only communicate with its own modules. An exception is the shared area to which each context has access.

- Each module may only access modules in lower layers of the matrix. Each module category becomes a layer in this sense.

Both rules support the decoupling of the individual modules or context and help to avoid cycles.

Project Structure for the Architecture Matrix

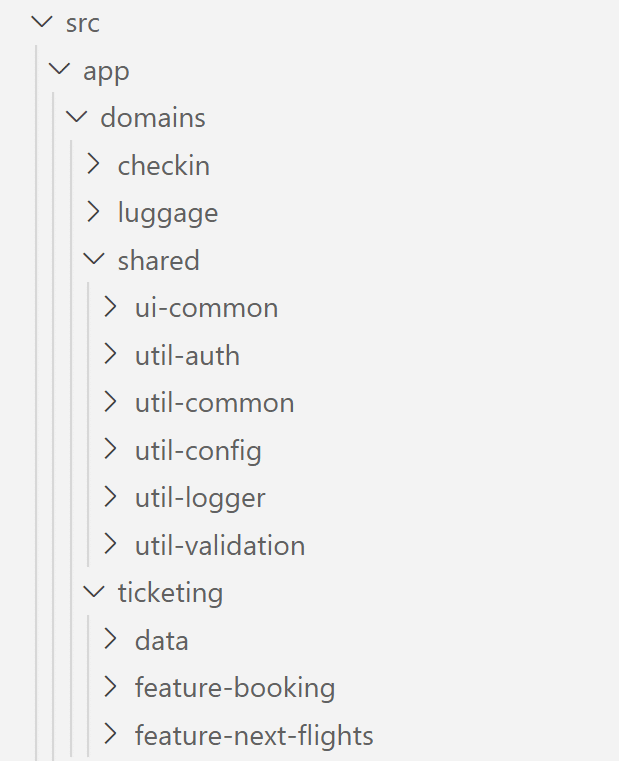

The architecture matrix can be mapped in the source code in the form of folders: Each context has its own folder, which in turn has a subfolder for each of its modules:

The module names are prefixed with the name of the respective module category. This means that you can see at first glance where the respective module is located in the architecture matrix. Within the modules are typical Angular building blocks such as components, directives, pipes, or services.

The use of Angular modules is no longer necessary since the introduction of standalone components (directives and pipes). Instead, the standalone flag is set to true:

@Component({

selector: 'app-flight-booking',

standalone: true,

imports: [CommonModule, RouterLink, RouterOutlet],

templateUrl: './flight-booking.component.html',

styleUrls: ['./flight-booking.component.css'],

})

export class FlightBookingComponent {

}In the case of components, the so-called compilation context must also be imported. These are all other standalone components, directives and pipes that are used in the template.

An index.ts is used to define the module's public interface. This is a so-called barrel that determines which module components may also be used outside of the module:

export * from './flight-booking.routes';Care should be taken in maintaining the published constructs, as breaking changes tend to affect other modules. Everything that is not published here, however, is an implementation detail of the module. Changes to these parts are, therefore, less critical.

Enforcing your Architecture with Sheriff

The architecture discussed so far is based on several conventions:

- Modules may only communicate with modules of the same context and shared

- Modules may only communicate with modules on lower layers

- Modules may only access the public interface of other modules

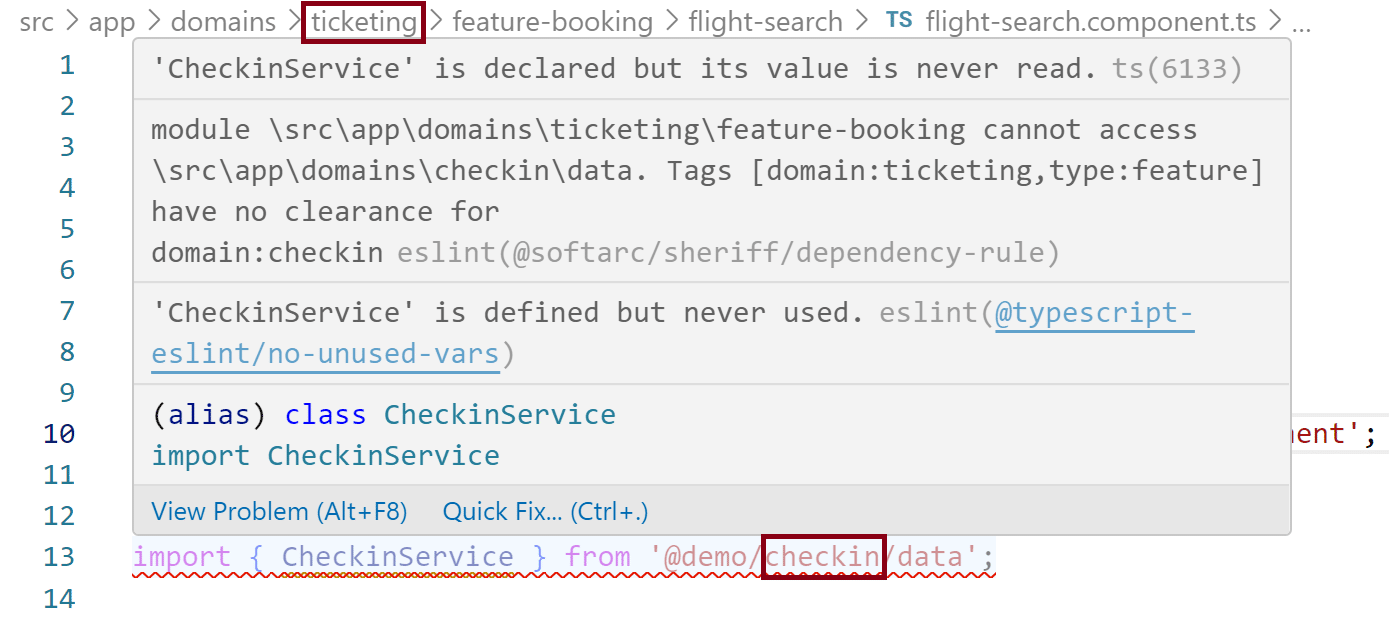

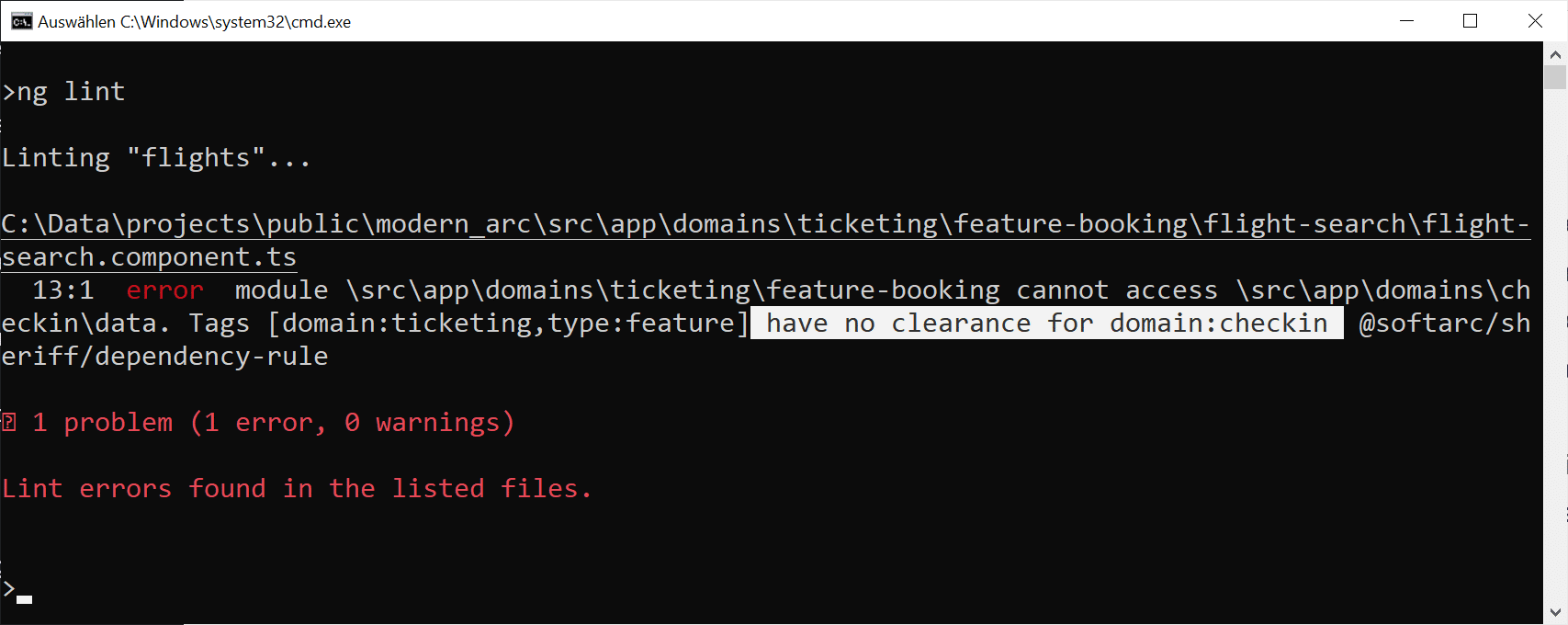

The Sheriff Sheriff open-source project allows these conventions to be enforced via linting. Violation is warned with an error message in the IDE or on the console:

The former provides instant feedback during development, while the latter can be automated in the build process. This can be used to prevent, for example, source code that violates the defined architecture from ending up in the main or dev branch of the source code repo.

The former provides instant feedback during development, while the latter can be automated in the build process. This can be used to prevent, for example, source code that violates the defined architecture from ending up in the main or dev branch of the source code repo.

To set up Sheriff, the following two packages must be obtained via npm:

npm i @softarc/sheriff-core @softarc/eslint-plugin-sheriff -DThe former includes Sheriff himself, the latter is the tethering to eslint . The latter must be registered in the .eslintrc.json in the project root:

{

[...],

"overrides": [

[...]

{

"files": ["*.ts"],

"extends": ["plugin:@softarc/sheriff/default"]

}

]

}Sheriff considers any folder with an index.ts as a module. By default, Sheriff prevents this index.ts from being bypassed and thus access to implementation details by other modules.

The sheriff.config.ts project's root defines folders representing the individual modules. Each module is assigned one or several tags such as type:feature or type:ui. These tags are the foundation for dependency rules (depRules) defining which module is allowed to access which other modules.

The following shows a Sheriff configuration for the architecture matrix discussed above:

import { noDependencies, sameTag, SheriffConfig } from '@softarc/sheriff-core';

export const sheriffConfig: SheriffConfig = {

version: 1,

tagging: {

'src/app': {

'domains/<domain>': {

'feature-<feature>': ['domain:<domain>', 'type:feature'],

'ui-<ui>': ['domain:<domain>', 'type:ui'],

'data': ['domain:<domain>', 'type:data'],

'util-<ui>': ['domain:<domain>', 'type:util'],

},

},

},

modules: {

root: ['*'],

'domain:*': [sameTag, 'domain:shared'],

'type:feature': ['type:ui', 'type:data', 'type:util'],

'type:ui': ['type:data', 'type:util'],

'type:data': ['type:util'],

'type:util': noDependencies,

},

};The tags refer to folder names. Expressions such as <domain> or <feature> are placeholders. Each module below src/app/domains/<domain> whose folder name begins with feature-* is therefore assigned the categories domain:<domain> and type:feature. In the case of src/app/domains/booking, these would be the categories domain:booking and type:feature.

The dependency rules under modules pick up the individual categories and stipulate, for example, that a module only has access to modules in the same domain and to domain:shared. Further rules define that each layer only has access to the layers below it. Thanks to the root: ['*'] rule, all non-explicitly categorized folders in the root folder and below are allowed access to all modules. This primarily affects the shell of the application.

Please pay some attention to the enableBarrelLess property. When set to true, everything within folders named internal will be considered an implementation detail of the respective module. That means it cannot be accessed from other modules even though the configured rules would allow it. When omitting enableBarrelLess or when setting it to false, Sheriff expects an index.ts in every module exporting the module's public API. Everything else is considered internal.

Lightweight Path Mappings

Path mappings can be used to avoid illegible relative paths within the imports. These allow, for example, instead of

import { FlightBookingFacade } from '../../data';to use the following:

import { FlightBookingFacade } from'@demo/ticketing/data' ;Such three-character imports consist of the project name or name of the workspace (e.g. @demo), the context name (e.g. ticketing), and a module name (e.g. data) and thus reflect the desired position within the architecture matrix.

This notation can be enabled independently of the number of contexts and modules with a single path mapping within tsconfig.json in the project root:

{

"compileOnSave": false,

"compilerOptions": {

"baseUrl": "./",

[...]

"paths": {

"@demo/*": ["src/app/domains/*"],

}

},

[...]

}IDEs like Visual Studio Code should be restarted after this change. This ensures that they take this change into account.

What's next? More on Architecture!

Please find more information on enterprise-scale Angular architectures in our free eBook (5th edition, 12 chapters):

- According to which criteria can we subdivide a huge application into sub-domains?

- How can we make sure, the solution is maintainable for years or even decades?

- Which options from Micro Frontends are provided by Module Federation?

Feel free to download it here now!

Conclusion

Strategic design subdivides a system into different sub domains that are implemented low coupled bounded contexts. This low coupling prevents changes in one area of application from affecting others. The architecture defines different modules per context, and the open-source project Sheriff ensures that the individual modules only communicate with eachother according to established rules.